How do people deal with life-changing situations such as life-threatening illness, loss or trauma? Many people react to such circumstances with an initial flood of strong emotions and a sense of uncertainty. However, most people adapt well over time. What enables them to do so? The term “Resilience” is used to describe this common adaptive coping. How do people manifest resilience? What can explain the individual differences? Most importantly, can specific resilience skills—behaviours, thoughts and actions—be learned and developed? These are some of the many open questions regarding resilience in different contexts that BOUNCE has set out to address.

Being resilient does not mean that a person doesn’t experience difficulty or distress. Emotional pain and sadness are part of the common experience of people who have suffered major difficult life events and trauma. In fact, the road to resilience, according to the APA (American Psychological Association) is likely to involve considerable emotional distress. Contrary to common belief, being resilient is not extraordinary, and as Ann Masten, one of the world’s leading scholars in the field of resilience, coined it: “Resilience is ordinary magic.” To date, there is still a lack of clarity as to what resilience is and how it operates. Does being resilient relate to an individual’s potential (capacity to engage in adaptive coping processes), process (adaptive reactions to adversity), or outcome (the final state achieved as the result of coping)?

Resilience as Potential

Some understand resilience to be a predisposition or an existing potential, before even facing an adverse situation. In this sense, Resilience as Capacity is the integration of the internal and external resources available to the individual facing adversity that may influence the effectiveness of the coping process, e.g., optimism, humor, cognitive flexibility, cognitive explanatory style and reappraisal, acceptance, religion/spirituality, altruism, social support, positive role models, flexible/healthy coping style, exercise, the capacity to recover from negative events, and stress inoculation.

Many studies show that the primary factor in resilience is having caring and supportive relationships within and outside of one’s family. Relationships that create love and trust provide role models and offer encouragement and reassurance that help bolster a person’s resilience. Several additional factors are associated with resilience, including:

- The capacity to make realistic plans and take steps to carry them out.

- A positive view of oneself and confidence in your strengths and abilities.

- Communication and problem-solving skills.

- The capacity to manage strong feelings and impulses.

Resilience as a potential is not a trait available solely to the individual—it can exist in groups as well. In a family, resilient characteristics may take the form of a sense of solidarity, involvement, warmth towards other family members, and cohesion among them. A resilient community would be one that offers supportive resources, and these may be based on a cultural context of resiliency reflected in the narratives, traditions or rituals of the individual or the community.

Resilience as an Adaptation Process

Resilience was defined by the American Psychological Association as “the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or significant sources of stress—such as family and relationship problems, serious health problems or workplace and financial stressors.” It posits that resilience is not a trait that people either have or do not have, and can be considered as an adaptation process. Resilient individuals may experience transient perturbations in normal functioning (e.g., several weeks of sporadic preoccupation or restless sleep) but generally exhibit a steady reimplementation of healthy functioning across time, as well as the capacity for constructive experiences and positive emotions. In this sense, resilience is more common than generally accepted, and there may be multiple ways of achieving resilience (Bonanno, 2004).

Resilience as Outcomes

Resilience can also be defined as the outcome of coping with trauma or adversity in the form of relative satisfaction with one’s quality of life and wellbeing. Resilience represents the ability to maintain a stable equilibrium, healthy functioning, subjective wellbeing, and satisfactory quality of life despite exposure to trauma. It means “bouncing back” from difficult experiences.

Resilience and Breast Cancer

Studies focusing on resilience in breast cancer patients show that women who maintained better body image had more positive future perspectives and reported less severe symptoms also reported higher resilience (Ristevska-Dimitrovska et al., 2015). In turn resilience may protect breast cancer patients against the development of psychological symptoms including depression and anxiety (Markovitz et al., 2015) and maintain high levels of subjective happiness after breast cancer. For the purposes of the BOUNCE project the consortium experts defined resilience in the context of coping with breast cancer as “a conglomerate of dynamic self-regulatory capacities that allow an individual facing adversity to mobilize and use internal and external resources over time in order to maintain or promote wellbeing. The construct of resilience is used in three ways: (a) As a personal capacity or potential; (b) As a post-trauma adaptive process or trajectory; (c) As an outcome of maintaining healthy functioning and subjective well-being despite exposure to adversity”

Coping with Resilience

When faced with such potentially life-threatening events each person engages coping strategies that can vary widely in their capacity to provide adaptive solutions and ensure optimal recovery with respect to the disease itself as well as to the patient’s overall quality of life. Coping strategies frequently vary depending on the stage and timing of illness (e.g. coping strategies when the person is diagnosed with breast cancer vs. after having received treatment). During the last decades, considerable progress has been made in the field of Health Psychology towards identifying factors that determine adoption of particular types of coping behaviors highlighting socio-demographic and cognitive-emotional (e.g., the persons own diverse perceptions of their illness), in constant interplay with ever-changing life circumstances. Moreover, it is recognized that intervention and/or prevention efforts should take into account both modifiable attributes as well as (constant) individual characteristics (such as sociodemographic, patient history, and cancer type) that may affect the person’s dynamics.

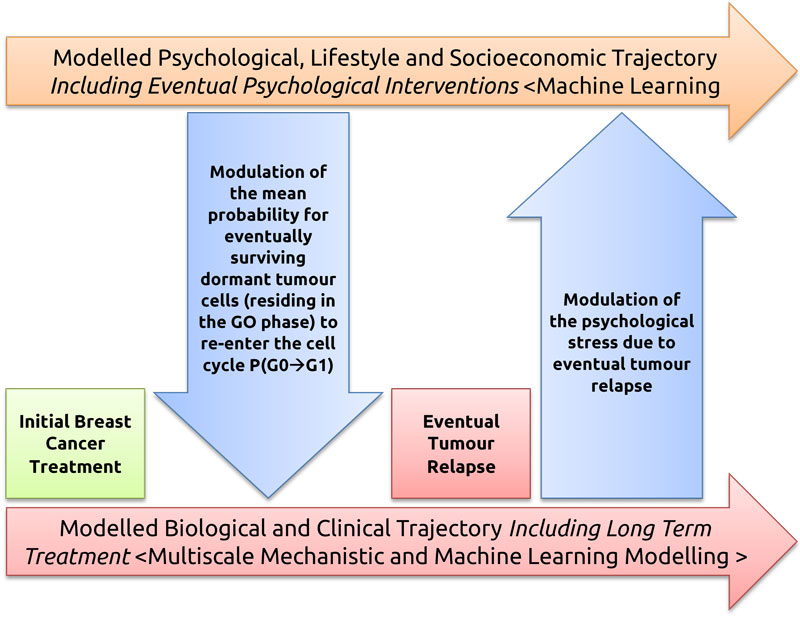

There is a growing need for novel strategies to improve understanding and capacity to predict the resilience of women to the variety of stressful experiences and practical challenges related to breast cancer. This is a necessary step toward efficient recovery through personalized interventions. BOUNCE will bring together modelling, medical, and social sciences experts to advance current knowledge regarding the dynamic nature of resilience, which relates to efficient recovery from breast cancer. BOUNCE will take into consideration clinical, cancer-related biological, lifestyle, and psychosocial parameters in order to predict individual resilience trajectories throughout the cancer continuum with the aim to eventually increase resilience in breast cancer survivors, help them remain in the workforce and improve their quality of life.

By Prof. Ruth Pat-Horenczyk, Hebrew University School of Social Work, Jerusalem, Israel

What is the meaning of resilience since being resilient does not mean that a person simply doesn’t experience difficulty or distress? There is a lack of clarity as to what resilience is and how it operates. Resilient relates to an individual’s potential (i.e., the capacity to engage in adaptive coping processes); it is a process (adaptive reactions to adversity), but also an outcome (the final state achieved as the result of coping). An effort to reach a consensus definition was made by a panel of prominent resilience experts who agreed on the following definition (Southwick, 2014): “The concept of resilience includes healthy, adaptive, or integrated positive functioning over the passage of time in the aftermath of adversity”.

The overreaching goal of BOUNCE is to incorporate elements of a dynamic, predictive model of patient outcomes in building a decision-support system used in routine clinical practice to provide physicians and other health professionals with concrete, personalized recommendations regarding psychosocial support strategies.