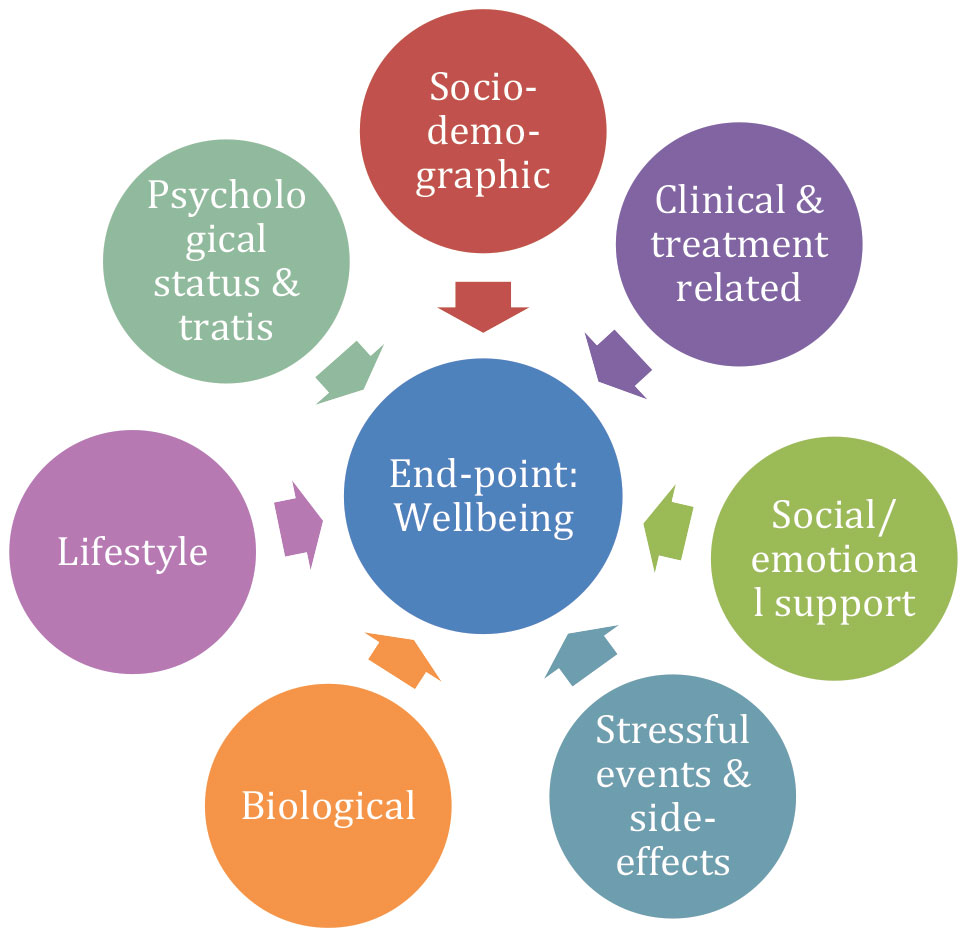

The overreaching goal of BOUNCE was to examine how women adapt to breast cancer and to illustrate paths to a successful recovery. To achieve this goal, we studied a wide range of variables related to the illness itself (clinical, biological, and treatment-related), patient family and social environment (actual and perceived), as well as social and psychological resources patients could rely upon to help them bounce back. The end product of these factors and processes defines the degree of resilience (as an outcome and a process) over the course of illness.

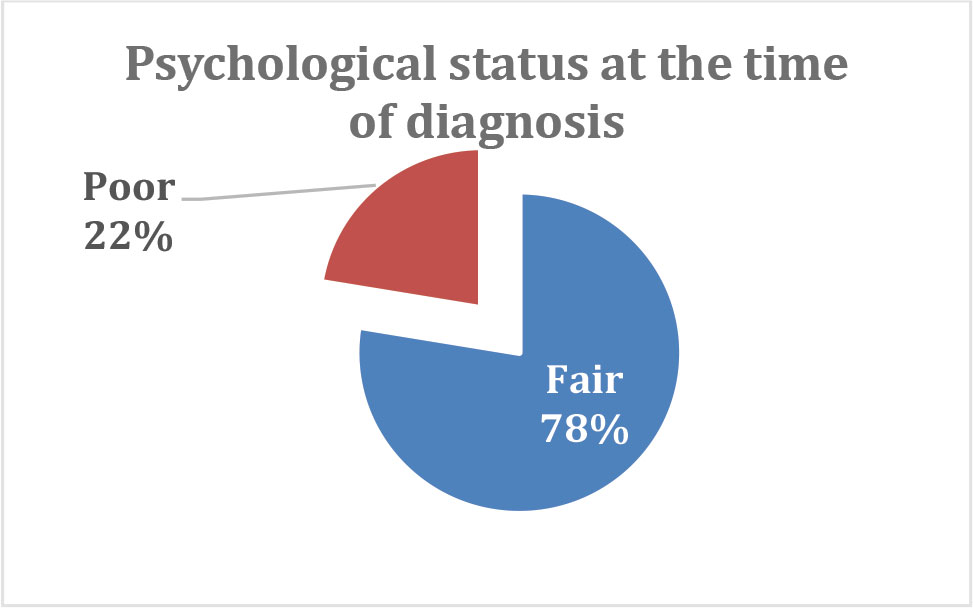

The baseline data collection of BOUNCE was designed to cover the psychological state of the patients as they take in, and attempt to mentally cope with the diagnosis of breast cancer. By design we studied women diagnosed with highly treatable breast cancers; that is to say, illnesses that may leave scars—both physical and psychological—although their threat to life itself is rather low. As expected only about one-fifth of the participating women reported significant symptoms of anxiety or depression at that time.

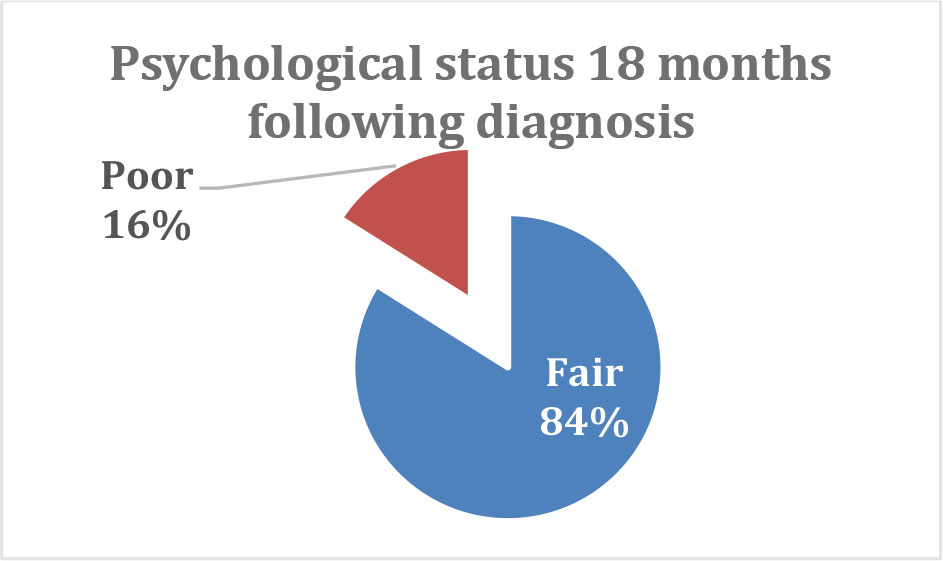

As time goes by, most women demonstrate successful adaptation, as indicated by the fact that fewer reported significant symptoms of anxiety or depression when queried again 18 months later.

These percentages, however, belie the diverse personal histories of adaptation known to take place during the critical first months of the illness. Among the most devastating manifestations during this period are negative emotional responses, ranging from fear and anxiety to anger, sadness, and hopelessness. These are also common symptoms of depression and are considered important determinants of well-being in the longer term. Fortunately, for most women, these emotional responses are temporary and subside within the first 6-9 months after diagnosis. For a relatively small minority, however, these responses persist longer (at least up to 18 months post-diagnosis). Others report fair emotional status early on, yet develop significant signs of poor well-being as time goes by, seemingly despite a positive medical prognosis, and after completion of cancer treatments.

So what set of factors predispose a woman who reports fair wellbeing when diagnosed with BC to later experience a significant increase in symptoms of anxiety and/or depression?

To address this problem in a flexible and sustainable manner, we developed and tested several Machine Learning (ML) models for optimal prediction of 12- and 18-month patient outcomes (in terms of symptoms of mental health and overall quality of life) by aggregating all available patient information from the early phase of illness (i.e., over the first 3 months following diagnosis).

Potential predictors included:

- patient-reported outcomes (i.e., mental health, distress level, health- and global Quality of Life, and functionality),

- sociodemographic variables (i.e., education level, employment status) and perceived social or health-related support,

- potentially stressful events taking place during the follow-up period (including perceived side effects),

- psychological characteristics and coping reactions (i.e. perceptions of illness, optimism, emotional self-regulation strategies, etc.),

- lifestyle factors (i.e., diet and exercise),

- clinical variables (cancer stage, molecular tumor type, type, and timing of medical treatments), and

- biological indicators of systemic processes (e.g., anemia, creatinine and bilirubin, blood cell counts, etc.).

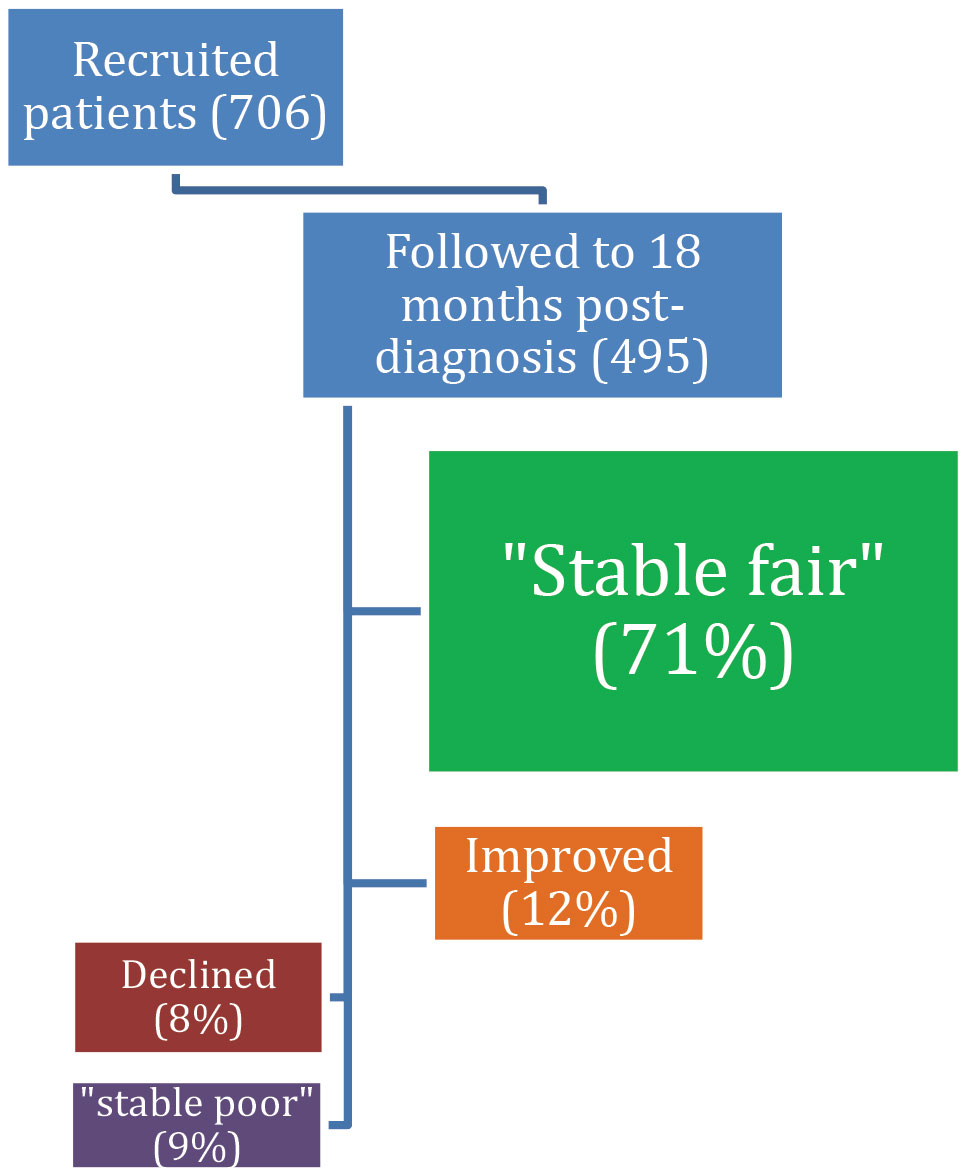

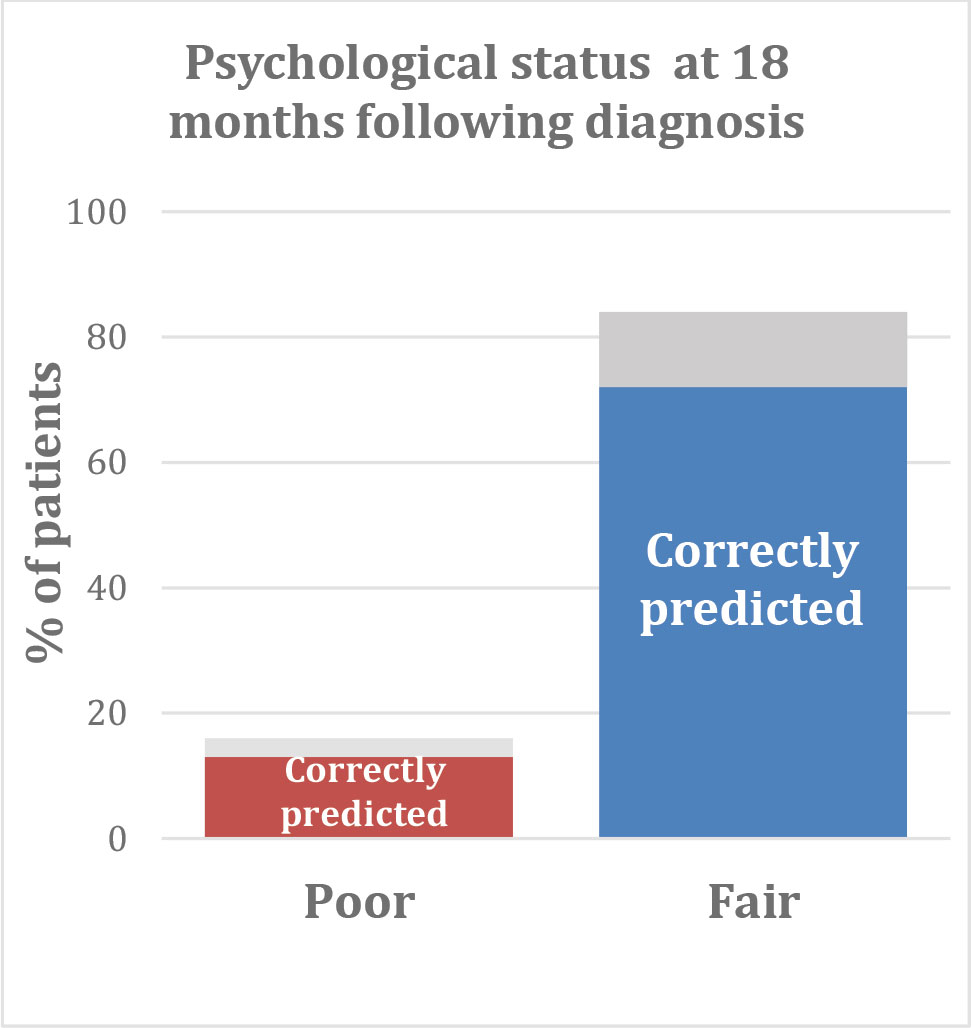

One of the best-performing Machine Learning models correctly predicted poor psychological status at 18 months following diagnosis for 71% of patients. The same model identified the patients who reported fair psychological status at that time with 76% certainty.

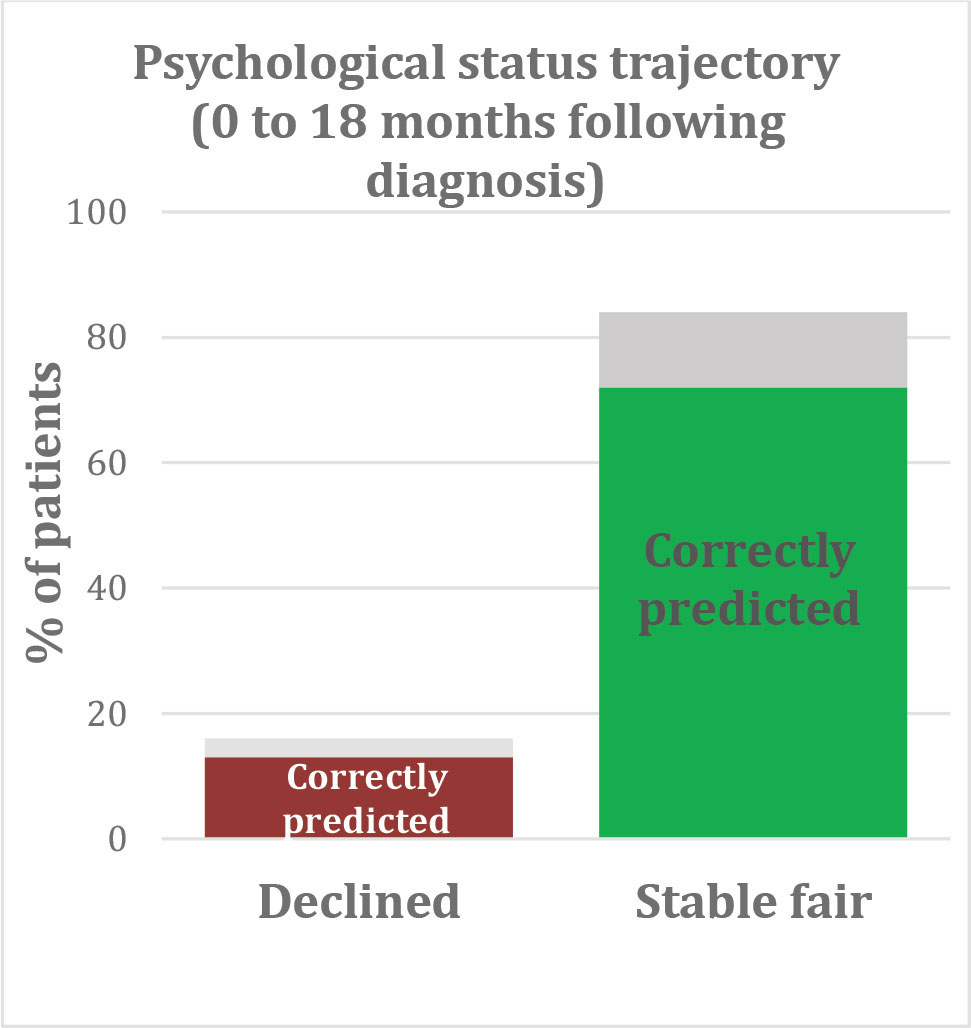

Α second well-performing model correctly predicted a significant decline in psychological status for 76% of patients and correctly identified patients who maintained fair psychological status throughout the 18-month study period with approximately 77% certainty.

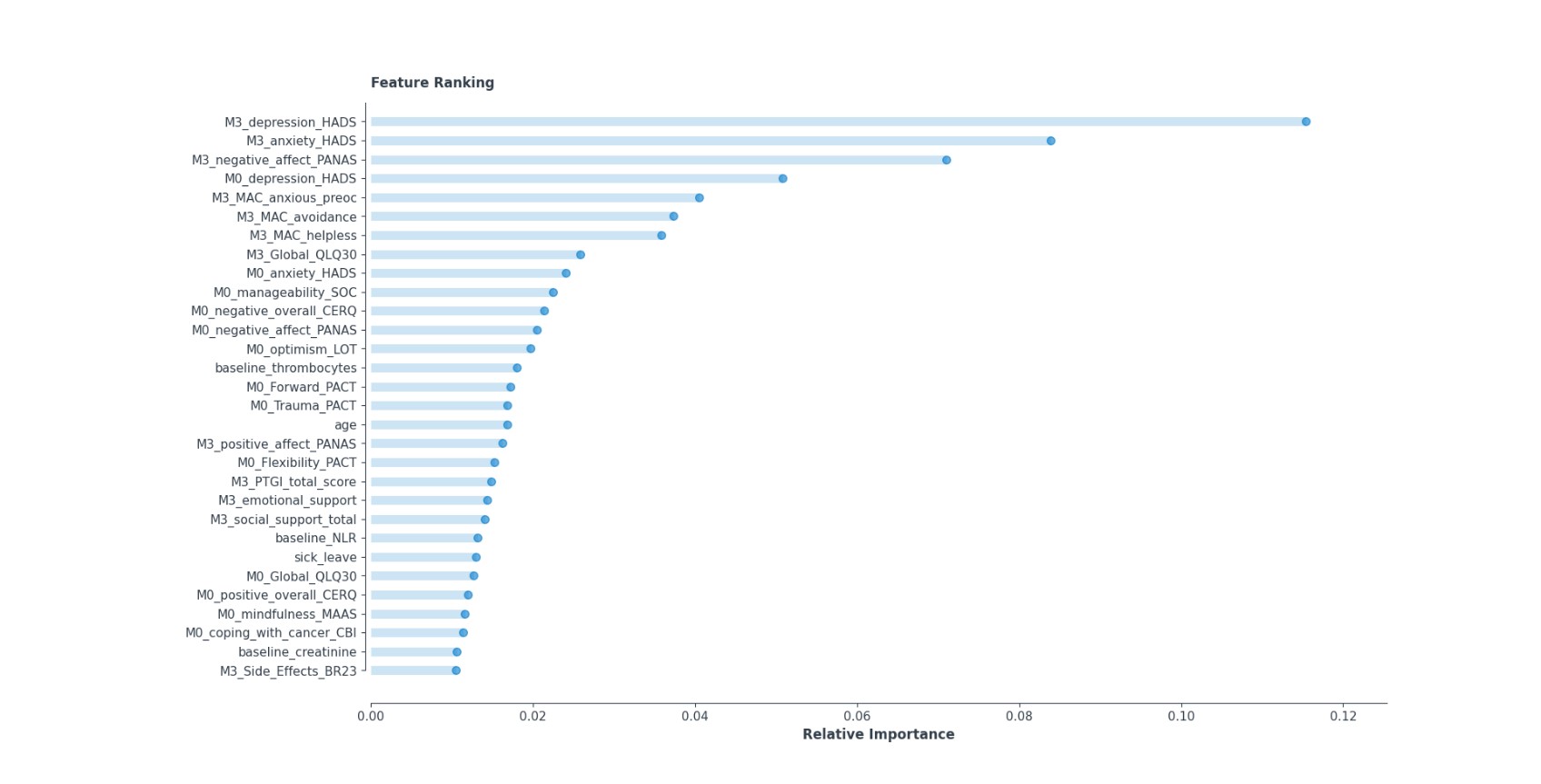

Most important predictors included variables measured shortly after the cancer diagnosis, as well as variables reported at the 3-month follow-up (that is, during treatment). They comprised lifestyle characteristics (at least moderate, regular exercise), trait resilience and other psychological characteristics presumed to be associated with illness adaptation, the emotional status of the patient (particularly on month 3), and specific, illness-related physical symptoms. In addition, two biological variables ranked among the important predictors: low platelet count (an index of the tendency of blood to coagulate and

form clots), and high neutrophil to leucocyte ratio which reflects a predominance of one type of immune system cells (neutrophils). These variables are ranked according to their relative importance for model accuracy in the figure below.

Conclusions

The design of Machine Learning models implemented in BOUNCE was guided primarily by the potential future clinical utility of forthcoming results. Thus, the supervised learning models included variables that can be readily available to practicing clinicians at oncology centers in most European and North American countries, namely medical, sociodemographic, and lifestyle variables integrated with a select set of psychosocial patient characteristics. Importantly, we employed a rigorous analytic approach to mitigate some of the commonly observed pitfalls of machine learning approaches, namely overfitting and poor model generalizability.

Especially with regard to significant psychological predictors, these can be grouped into 6 major classes:

- negative affect at the time of diagnosis and soon after (i.e., when most women have undergone surgical treatments as indicated and most have already started chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy);

- available strategies for effective coping with cancer and the person’s readiness to adapt;

- a sense of control over the illness and a general optimistic stance toward unforeseen life events;

- social and family support;

- certain lifestyle factors (i.e., exercise);

- the severity of certain physical symptoms and treatment side-effects.

These findings are in accordance with the major psychological theories about adaptation to severe illness, including BC, such as the Common Sense Model1 or the Transactional Stress Model2.

Our results highlight the importance of early psychological responses to cancer diagnosis and related treatments. The first few months following diagnosis can be considered as part of the acute phase of the disease, where pre-existing risk psychological traits can play a significant role in determining subsequent mental health. On the other hand, positive traits may be equally important in thwarting the impact of the disease on mental health. These may be even more important than negative traits because they could potentially be reinforced with the aid of health professionals at the first crucial visits of the patient.

The next step of our research was to develop analytic approaches toward specifying personalized profiles of “strong” and “weak” types of psychological and lifestyle resources which could be linked to appropriate clinical recommendations for health care professionals. This approach is outlined in the next article of this Newsletter.

Α second well-performing model correctly predicted a significant decline in psychological status for 76% of patients and correctly identified patients who maintained fair psychological status throughout the 18-month study period with approximately 77% certainty.

Most important predictors included variables measured shortly after the cancer diagnosis, as well as variables reported at the 3-month follow-up (that is, during treatment). They comprised lifestyle characteristics (at least moderate, regular exercise), trait resilience and other psychological characteristics presumed to be associated with illness adaptation, the emotional status of the patient (particularly on month 3), and specific, illness-related physical symptoms. In addition, two biological variables ranked among the important predictors: low platelet count (an index of the tendency of blood to coagulate and

form clots), and high neutrophil to leucocyte ratio which reflects a predominance of one type of immune system cells (neutrophils). These variables are ranked according to their relative importance for model accuracy in the figure below.

References

1Leventhal, H., Halm, E., Horowitz, C., Leventhal, E.A., & Ozakinci, G. (2005). Living with chronic illness: A contextualized, self–regulation approach. In S. Sutton, A. Baum & M. Johnston (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of health psychology (pp. 197-240). London: Sage.

2Lazarus, R., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

By Panagiotis Simos, George Manikis, Konstantina Kourou, & Evangelos Karademas, Computational Biomedicine Laboratory, Institute of Computer Science, Foundation for Research and Technology-Hellas